In all of my Google research, I realized that Liam really did not have features of these known genetic disorders. Most of them sounded pretty severe and the children had obvious deformities. There was one thing, however, that I did notice in Liam that I had not seen before – strabismus (crossed eyes). When I first read this word strabismus, I had no idea what it meant. I looked it up and thought “well that isn’t something that Liam has.” Nonetheless, I still went about my examination of his photographs and noticed that his eyes were not quite straight. I observed him in person and realized that his eyes did not seem to focus on an object or my face together. One eye would kind of drift off a little. It was subtle, but it was there. We were off to yet another specialist, the pediatric opthamologist. Our initial visit was unsettling as she diagnosed him with pseudo-strabismus, a condition where the eyes appear to turn inward due to having a flat bridge of the nose or epicanthal folds (skin that folds over the corner of the eyes). The opthomologist was certain that this was the case with Liam and uttered those now irritating words “we’ll keep an eye on it.” I read a lot about strabismus and how to detect it and I felt certain that this was something that was happening to Liam. I also read that strabismus is commonly associated with all forms of metopic synostosis as the fused skull restricts blood flow and sometimes brain growth in the frontal lobe and puts pressure on some part of the brain that affects vision. Unfortunately there was nothing I could do but wait until the condition worsened and it became obvious to everyone that he in fact had strabismus.

Over the course of several months Liam’s eyes turned inward and he became severely cross-eyed. This was so painful to me. My beautiful child was not going to be seen as beautiful by strangers. People stared. Children asked their parents “are my eyes crossed like that baby’s?” I overheard two women at the pool refer to him as “creepy.” We had no photos of him with straight eyes. Taking pictures was a reminder of the pain he may face growing up with “crazy eyes.” We went back to the opthamologist. She recommended that we use eye drops to dilate his stronger eye, making vision in that eye blurry, which would force his brain to use his weaker eye. Once the brain turns off the weaker eye, a child can lose sight in that eye permanently if it is not treated. The goal of treatment was to try and increase strength in both eyes and then Liam would have eye muscle surgery to align his eyes. He would most likely never truly use both eyes together, which would deprive him of depth perception. The surgery would be largely cosmetic and, in Liam’s case, he would probably require more than one surgery to keep his eyes straight. Strabismus can occur for a couple of different reasons and, unfortunately, in Liam’s case it was neurologically based. This means that his brain cannot integrate the two images taken in through the eyes and consequently shuts the weaker eye off to avoid seeing double. This was viewed as an unchanging situation and, while aligning his eyes through eye muscle surgery would help, it would not likely alter his brain’s ability to integrate two images into one and the problem would return.

Liam also began pediatric physical therapy following his nine-month check up to work on his motor skills. We met with the physical therapist weekly and she would teach us exercises to help Liam develop a variety of gross motor skills including unassisted sitting, low kneeling and tall kneeling (did you know that was a skill?), pulling himself to a standing position, “army” crawling and eventually crawling on all fours, cruising, and finally walking. We worked with him several times a day at home doing these exercises. Liam mastered sitting at 10 months, crawling at 12 months, and walking at 18 months. All later than average but still within the very outskirts of “normal.” To us this was not normal. We did not know of one other healthy child that didn’t walk until 18 months. It seemed like all of the babies we knew around his age were cruising past him, leaving him behind.

Liam was still not eating well and was maybe only 16 pounds at a year old. He was small and frail and in hindsight, not that interactive. He was a snuggly, loving, happy baby and to my recollection made eye contact, had a social smile, and babbled on time. It even seemed as if, for a while, he was learning to say “dada.” At least he was babbling “da, da, da, da, da” all of the time. Around 11-12 months of age, Liam underwent his first multidisciplinary developmental assessment. This was a ½ day’s event and included lots of different specialists from neurologists, speech pathologists, occupational therapists, etc. At the end of this assessment this team of specialists agreed that Liam seemed to be developing within the realm of normal but had a slight motor lag. He was progressing with physical therapy and they felt that he would catch up in time. It was the opinion of the neurologist and geneticists that his trigonocephaly was a minor anomaly that was not contributing to his motor lag. Despite this promising prognosis I still felt worried. My mama gut was telling me there was something really wrong. I felt guilty that I couldn’t accept their words of encouragement and believe that he would be okay. Somehow I knew he would not. I hated myself for thinking about him in that way but I couldn’t convince myself otherwise.

Liam received his 12- month vaccinations, including the MMR shot and Varicella (chicken pox). At this point I had reservations about vaccinating him further. He seemed sick all of the time and weak. I thought I had read that you should avoid vaccinations when a baby has a temperature or respiratory illness. Liam always had these things. The doctor said it would be okay, he was well enough for the shots. I wanted to say no, but I didn’t have the courage. I didn’t really have a scientific reason for saying no. It was just a mama gut thing and probably “media hype” about autism and vaccinations that was causing me fear. I trusted in the knowledge of the pediatrician and felt sure they would not be continuing the MMR shot if it was really contributing to the epidemic of autism…or would they? They had gotten some things wrong up until this point. I was losing faith. I still consented to the shots. I wasn’t ready to stand up to the system. The nurse gave the shots in Liam’s arm instead of his leg. He didn’t tell me he was going to do this. It all happened so fast I couldn’t stop him. Liam’s arms were so scrawny and frail it seemed like the needle would go all the way through. “Why did you give it in his arm?” I said with alarm. “At 12 months babies are starting to walk and we don’t want their leg to be sore and discourage their walking.” “You idiot! My baby just started to crawl. Don’t you know that? I don’t want his arm to be sore and discourage his crawling!” Okay, I didn’t say that but I thought it. I wanted to say it. I was starting to get pissed, everything was going wrong with my child and I had no answers! All of his symptoms were too mild to really sound off alarm bells or lead us to an answer, but severe enough to be obvious to everyone around him that something was wrong.

After Liam’s appointment I drove him back to day care. On the way he fell asleep, it was about 10 in the morning. I told the day care staff that he had had his shots and then fell asleep. He had some Tylenol they could give him if he seemed in pain or developed a fever. I went back to work. A few hours later the day care called. Liam had not yet awoken. They tried to wake him, but he wouldn’t stay away. We agreed to let him sleep and “keep an eye on him.” At 5:00 p.m. I picked him up. He was still sleeping. I took him home. Still sleeping. We tried to wake him, to get him to eat. He would slightly open his eyes but then go back to sleep. He had a slight fever. Later that evening I called the advice nurse and we were sent to the emergency department. Again, no real understanding as to why he would not wake, but it was considered a likely “adverse reaction” to his shots. He was given some fluids because he would not eat and was dehydrated. We took him home again. I was scared. I couldn’t believe it. I was again mad at myself. “How could I have let them give those shots?!” Every fiber of my being was telling me to say “NO!” When would I learn my lesson and stop taking his life so lightly? How could I be screwing up so much? Was I really that bad of a mom? All my life I wanted children. Now that I had one, I was ruining him.

Liam did eventually wake up, but he was not the same. He was drifting away from us before the shots and now he was gone. A couple of weeks after his shots Liam underwent his second developmental assessment through our local early intervention program – basically special education for children birth to five. I had faxed this program the results of his first assessment to see if he would qualify for services. Based upon those results he did not. At his second assessment I remember the evaluators rolling a ball to Liam. He would bat it back to them but would not look at them as he did this. I remember them commenting on this, making note of it. In my mind I heard them saying, “This baby has autism,” that’s what I heard in their comments about his consistent failure to look at them. Of course they did not say this, I was reading between the lines with fear. I so wanted to get up the courage to say something, to ask, “Do you think he could have autism?” But again, I said nothing. I was not ready to speak those words, to hear what they thought. Based upon this evaluation Liam did qualify for services due to delays in gross motor development, communication, and social emotional development. This assessment was done only about a month after his first one. Had he really changed that much since his shots or was the first assessment just woefully inaccurate? I knew in my heart that he did have delays in these areas and I was glad we were going to get some help.

To be continued

In this photo, Liam is around 9-10 months old. If you look closely you can see that his eyes are not perfectly straight, with his eye to the left turning slightly out. This was one of the photos that I examined after first learning about strabismus and trigonocephaly. Photos of him at this age were a little deceiving because he was not always looking right into the camera, so it was hard to determine if his eyes were misaligned or if they just appeared that way due to the angle of his gaze. I learned that one of the best ways to determine if a child has strabismus is to look for the reflection of the flash (the little dot of light). This should be in the exact same spot on each eye. You can see that, in this photo, the reflection is in the center of one eye and slightly to the right in the other.

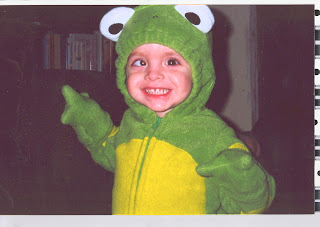

Here Liam is all dressed up for Halloween at nearly 21 months of age. You can see the dramatic change in his eyes. At this time, we were using the dialating drops to try and force the his brain to use the "turned off" (crossed) eye. Even with his crossed eyes, Liam is still an adorable little guy.

This is Liam at age 2 years. You can see that his eyes continued to worsen over time. This is how many of his photos looked at that age. Heart breaking.

Liam at 16 months getting lots of help from family during a family reunion. Everyone spent tons of time with him practicing walking. By the end of that week Liam took 20 steps by himself. We were so excited. After we returned home and there wasn't a constant barrage of physical therapy, Liam regressed and wasn't able to take unassisted steps until 18 months of age. Just goes to show you more intensive help matters.

Gosh Angie,

ReplyDeleteI had only hints of this story. The comments of people around you... and your feelings as a mother, strike me deeply. Why anyone would ever be anything but supportive is so sad. I can't imagine how you must have felt. Thanks for writing this, it helps me. Such a clear and straightforward account of what must of seemed an endless confusion.

I look forward to your next account. Our time differences mean your blog's going to be getting me up early in the morning (I checked it last night, but here it is.... this morning.)